[Back in 2009, as part of my Ten Questions Series, I interviewed Chris Anderson, who was then the Editor-in-Chief of Wired Magazine (he since left to work on other things, namely, a drone-making startup). Re-reading the interview recently, I was delighted to see how much of it has stood the test the time, hence I’m reposting it again, here below.]

Ten Questions For Chris Anderson

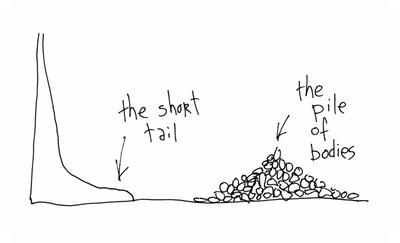

Chris Anderson is the Editor-in-Chief of Wired Magazine, the great tech & culture publication from Conde Nast. He first came to my attention when he published the book, The Long Tail, which talks about Power Laws and the Internet, especially marketing and the possibilities that the Web opens up for everybody. His latest book, “Free”, talks about the new economies of the Internet, where the default price of everything, as he reminds us, is “set at zero”. He kindly allowed me to interview him.

1. First off, let’s plug your latest book, “Free”. Tell us what it’s all about?

It’s about how technology has turned “free” from a marketing trick to

a new economic model. The digital economy is full of paradoxes,

including the big one: it seems that practically everything online is

free and yet we’re told that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Even more mystifying, jokes like “we lose money on every sale and make

it up on volume” actually describe the business models of such

massively profitable companies as Google.

The book explains the underlying cost economics that allow so much to

be free online, and the business models built around that. It

contrasts 20th Century Free (simple cross-subsidies–you’re paying,

sooner or later) with 21st Century Free (wildly indirect

cross-subsidies–somebody’s paying, but it’s probably not you). And it

focuses on “Freemium” (free+premium), which I think is the first

really new business model of the web and the future of Free online.

2. I think a lot of people have seemed to miss the point of your book, especially people in your business. To me, the point of your book is not about “Free VERSUS Paid”, but a concorde between “Free AND Paid”. As a cartoonist who swings between “Free” and “Paid” quite happily, I don’t see a conflict between the two. Like I said before,

Any profession is in constant, ever-changing negotiation with “Free vs Paid”. When does your lawyer friend offer you free legal advice, and when does he start charging? Ditto with your heart-surgeon pal you play tennis on Tuesdays with. Musicians give their music away for free on MySpace, but charge for the CDs, live gigs and the t-shirts. Petroleum Industry consultants might give 5% of their stuff away for free, just to drum up some new business, but then charge top dollar 95% the rest of the time. In Internet circles, the 95-5% converse is often true. Everyone has their sweet spot. Cartoonists are no different.

In other words, “Free” has always been with us, “Free” is nothing new. So why do you think it’s so hard for people to get their heads around it? Why all the controversy? What are they afraid of?

Well put. I think there are two classes of people who are afraid or

skeptical of Free: those who grew up before the web (ie, olds like me)

and people whose industries are threatened by the web (ie, media

people like me). Many in my generation or profession (mostly, I hope,

those who haven’t read the book) assume that Free is something of a

Ponzi scheme. Meanwhile, my kids are also appalled that I wrote a book

called FREE, but not because it’s wrong/scary, but because it’s so

freaking obvious.

Needless to say, they’re both wrong. Free is neither a mirage nor is

it self-evident. Instead, it’s an essential, but complicated,

component of a 21st century business model–not the only price, but

often the best one.

3. A lot of blog pundits out there spend a lot of time pontificating about “What is the future of media?” You, who probably knows more than most about this, seemed to almost offend this journalist from Germany when you answered, “I don’t know”. Reminds me of a jazz musician from the 1950s (his name escapes me) who was asked by a journalist, “Where do you think jazz is going?” To which the musician replied, “If I knew where it was going, I’d already be there.” Seems to me that the more you talk about the “uncertainty” of it all, the more peoples start demanding “certainty” from you. Odd, no?

The main problem with professional media is that we’ve lost our

quasi-monopoly on consumer attention. What’s worse, we’ve lost it to

an indistinct cloud of mostly non-media voices, from blogs to Facebook

to Twitter to YouTube. These amateurs, mostly producing without any

interest in a business model at all, are narrow where we are mass,

many where we are few and free where we are paid. They are not “media”

but they compete with media. That’s why strict adherence to terms

doesn’t help–it’s fifth column vs fourth estate!

I think that this is a moment where the sacred vocabulary of

professional media (“journalism”, “news”, etc), which we use as

incantations to differentiate ourselves from the unwashed horde, now

obscure the path forward more than illuminate it. Some of what we do

still has great value and perhaps always will: original information,

accuracy, analysis, great writing, edtiting, etc. But it is arrogant

to assume that only we can do that stuff, or that we know best what’s

“fit to print”.

I don’t know what the future of professional media is, but I am sure

there is one and am excited to participate in the many experiments

that will reveal what it is (obviously there is no one model or a

silver bullet solution–instead the future is going to messy and

multivariate, which is why it’s so scary for many). One thing that is

sure is that it’s not hoping change will stop or wishing to reverse

the tides of history.

4. You’ve become one of the great advocates of “Free”. Yet the people who sign your paychecks, well, they’re not in that business. They’re trying to sell magazines and advertising space. Similar deal with the people who publish your books. Does this create a lot of tension behind the scenes? Or do you try to educate them? How do these two different worldviews work together?

Actually, they *are* in that business. Most companies understand that

Free is the best marketing, which is why the magazine company I work

for makes its websites free and my book publisher gives out thousands

of free books each year to influentials. Of course they’re in the Paid

business, too. But that’s the point of the book: it’s getting easier

and easier (thanks to near-zero marginal cost of digital

distribiution) to use Free to promote Paid. In the magazine world, we

charge some customer groups nothing (web) or very little (print

subscribers) and other customer groups (advertisers) a lot.

Books are more conventionally priced, but when Hyperion agree to

publish a book called FREE by me, they knew what they were getting

into. It was a negotiation, to be sure, about how far we would go, but

using Free in one way or another was always part of the plan.

5. You’ve got your Editor job, you’ve got your book deals, you’ve got your blog, you do a lot of speaking gigs… As your name gets more and more known, are you having trouble keeping up with everything? What’s your coping mechanism? How do you find the balance?

Plus the five little kids, the two startup companies on the side, etc.

Obviously, balance is a distant goal. In the meantime, I delegate,

work all the time, hardly sleep, totally ignore politics, sports and

pop culture, neglect my family too much and probably don’t do any of

my jobs as well as I could. But these are exciting days, and if ever

these was a time to be overextended this is it.

6. Everybody knows you now as “Editor In Chief of Wired”. That’s a pretty big deal. I’m curious how you got there. Did you start off in journalism, with a career path all planned out, or was it a “random act of traction”? Tell us about your background.

Trained as a physicist (Los Alamos, etc). As I was heading to grad

school, realized that I wasn’t a very good physicist and that the

high-energy experiments that I was working on were running headlong

into a financial crisis (cost of accelerators rises with the square of

the energy of the accelerator–many $ billions). Bailed and went to

the science journals instead (Nature, Science). Then recruited to

start Internet coverage at The Economist in 1993 (remember the Web

started in a physics facility, CERN, so I was an early user). Three

years in London covering tech for the Econ, then three years in China

covering Asia, then to NYC as US Business Editor. Then recruited in

2001 (darkest days of the post dot.com crash) by Conde Nast to run

Wired.

So from physics geek to the Devil Wore Prada. “Random acts of traction” indeed.

7. Wired makes the lion’s share of its money via advertising, of course. The more I think about advertising-funded media, the less I think it’s just about offering “space” and “eyeballs”. At some level, the magazine’s job is to provide a context, a situation, an arena, that makes brands appear more “interesting”, than if they went somewhere else. The goods news is, this is a great opportunity for magazines. The bad news is, it’s really, really hard. What’s Wired’s attitude on this? Are you trying to push out the limits of advertising, with the same verve you try to push out the limits of tech and culture?

We should, and if we are to thrive, we must. We invented the banner ad

in 1995 (sorry!) and I hope we’ll help invent some of the ad units

that work best in the next era, too. Much of the innovation will be

online, but not all of it. And once devices emerge that allow a

magazine-like experience with digital delivery (Apple tablet?), the

distinctions between the two will blur.

8. As anyone who reads your stuff will know, human civilization in the middle of great changes, with media at the vanguard. And when great change happens, some things get harder, some things get easier. What’s getting easier about your job? Harder?

Easier: experimenting. Harder: predicting.

9. We all know what Wired is, and it’s great. But what do you want Wired to be, that it isn’t already? Just curious.

We’re known for being innovative in magazine making. I’d like to be

equally know for innovations in business models.

10. A lot of bright kids out there, just leaving school, would love to have your job one day. Hell, a lot of them would love to just have a job on your team. What advice would you give them, in order to make that happen?

Don’t wait to be given a job to do something cool. Follow your

passions, create something every day, take chances and try to be the

best in the world at something, no matter how tiny and trivial.

Nothing impresses me more than initiative. And there has never been a

better time to take it.

On a more prosaic note, I think that leading people is perhaps the

most important skill these days. My business card says “Editor in

Chief”. I suspect that if any of my children follow in my footsteps,

their card will say “Community Manager”. Helping (and inspiring) other

people to do cool stuff is what an editor does, and when you take it

out of a purely professional media context that looks more and more

like effective community management. It’s a great skill and I admire

those who do it well.