The more you try to show, the less people see.

The more you try to say, the less they hear.

The more you try to explain, the less they understand.

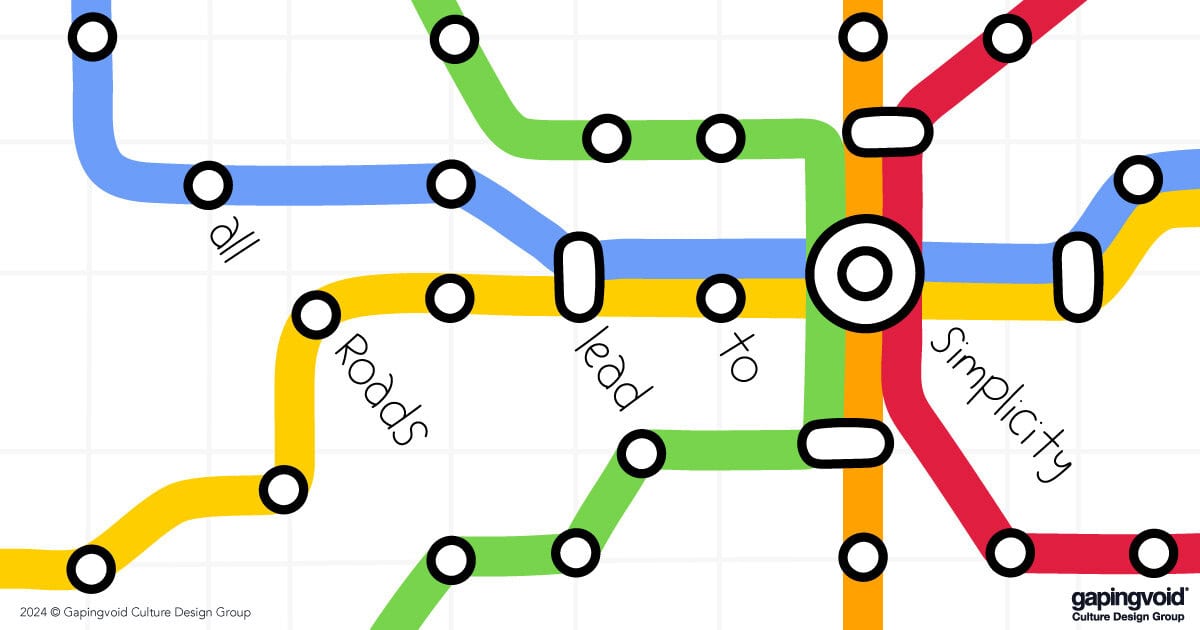

The London Underground figured this out in the early 1930’s. At the time, tube maps were engineering marvels of accuracy. Every turn, every station was to-scale and plotted with geographical precision. Perfectly accurate maps that were perfectly useless.

Then Harry Beck, an electrical draughtsman, proposed something radical. Instead of geography, he drew inspiration from electrical circuit diagrams. Clean lines and 45-degree angles. He opted for visual clarity over physical reality.

The authorities initially rejected it. “Too radical,” they said. “The public won’t understand it.” What if we oversimplify and it becomes harder to follow?

But it worked. So well that nearly every transit system in the world copied it.

The thing about accuracy is that it’s a trap. A seductive one. It feels safe. It feels professional. It feels like creating more understanding. But Beck understood something profound: humans don’t need precision, we need clarity.

Think about your organization.

How many vision statements try to please everyone instead of inspire anyone? How many strategies include every possibility instead of the few that matter?

Many of us get stuck thinking we have to add detail for accuracy’s sake. More analysis. More data. More bullet points.

But the measure for success isn’t accuracy. It’s movement. Does this make people act? Does this drive the change we’re seeking?

For the most part, every extra detail we add is another reason for someone not to remember it.

Just like Harry Beck with his subway map, sometimes the most strategic thing a leader can do is decide what to leave out.

The proof?

It’s hanging in every subway station in the world.

This is such GREAT insight. Thank you.

I try to overexplain!